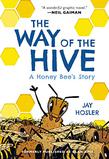

When readers first meet Nyuki, the protagonist of Jay Hosler’s new graphic novel, The Way of the Hive (HarperAlley, April 20), she’s a smart-mouthed larva who isn’t too keen on metamorphosis. Under the tutelage of her sister Dvorah, however, she reluctantly pupates and then emerges as a worker bee, physically if not mentally ready to take on the sequence of roles all workers perform as they age through their life cycle. Nyuki ultimately ventures from the hive, bumbling into maturity with enormous charisma and teaching readers an astonishing amount about honeybee biology as she goes. The Way of the Hive was initially self-published as Clan Apis in 1998; in between, Hosler has explored other stories that combine science and comics, including Last of the Sandwalkers (2015) and Optical Illusions (2008), the latter being the first comic funded by the National Science Foundation. He spoke with Kirkus about bees, storytelling, and existential questions from his home in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, where he is chair of the biology department at Juniata College. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me how you came to the story.

What led me to graduate school was neurobiology and animal behavior. Those are two of the big classes I teach [at Juniata]. I made a transition through rotations into a lab [that] studied honeybees and insects in general. Then, once I’d finished my degree, I had set up a postdoc on honeybee learning. I thought I should probably know a little bit more about this bee biology. With that baseline of interest, I read Mark L. Winston’s The Biology of the Honey Bee. And that’s when the narrative possibilities popped open for me.

I was primed at that moment. When I was in graduate school, I had a daily comic strip for the Notre Dame newspaper and a weekly strip for the Comics Buyer’s Guide. I was doing six strips a week. A lot of it was banal, college-y kind of humor. But I really wanted to contribute something good to the medium, because I love it, right? I was always communicating in pictures, even with my slide presentations and whatnot. So I wanted to do something unique. It was the 1990s, and everything was extreme. I really wanted room for stories that were an adventure story but a little gentler. For me it was about exposing people to a world.

I was primed at that moment. When I was in graduate school, I had a daily comic strip for the Notre Dame newspaper and a weekly strip for the Comics Buyer’s Guide. I was doing six strips a week. A lot of it was banal, college-y kind of humor. But I really wanted to contribute something good to the medium, because I love it, right? I was always communicating in pictures, even with my slide presentations and whatnot. So I wanted to do something unique. It was the 1990s, and everything was extreme. I really wanted room for stories that were an adventure story but a little gentler. For me it was about exposing people to a world.

The Way of the Hive is really about my fear of death, wrapped up with a fear of change. That anxiety, that part of the book, is autobiographical—it’s deeply personal and human. But I’m showing you a world in which organisms live in a house built by their own bodily secretions, right? They walk around on six legs and have wings sprouting out of their back. They smell and taste with feelers sticking off the front of their head. That’s the kind of world that I love exploring and discovering.

In about 1996 I applied for a Xeric Award, which was a grant that was set up by Peter Laird, of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle fame. I had also applied for a three-year grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health to fund my research. I found out the same week that I got both. That grant actually set me up to do little brain surgeries on honeybees. It was going to pay for my salary and everything for three years. And then I got this little $1,500 grant to self-publish a single issue of a comic. And that’s the one that I was really excited about.

Let’s talk about your creation story, about the world flower.

I grew up pretty religious. I’m not anymore, but I understand the comfort of it. And I understand near the end of your life, hoping for something that’s beyond that. In the bees’ mythology not only is there a myth for creation, but there is a myth for what happens after [death]. Nyuki doesn’t get to live forever. But she’s come to understand that part of her can. You know, I try to avoid things like “the circle of life,” and I don’t want to start singing. But the fact that bits and pieces of all of us, after we die, shift out into the world and become bits and pieces of other living things? That to me is a great comfort, to know that I’m a part of that.

How much contact do you have with your readership?

In the early 2000s, when I was going to comics shows, I heard a lot from kids. And I was always struck by how enthusiastically they would come to my table and tell me everything that they learned. But they wouldn’t say, “I learned this,” they would say, “The bees can do this.” They would almost be repeating back to me what I had written, [with] this bubbling enthusiasm.

I once had two women who were college students [who] said that their father read it to them frequently. And as they talked about it, they started tearing up about the death of Nyuki. Now this is an organism that up until that book they may have swatted with impunity. So I have managed to help forge an emotional connection with the subject of my science. This is one of the things I think we, as scientists, don’t do very effectively. We do amazingly tedious work in order to collect data. Why do we do that? We do it because we love it. In science, I think one of the great problems in communicating is we focus on our methods, right? Oh, I did this. And I did this. And I did this. And as I tell my students, “Nobody cares. Absolutely zero people care. Nobody cares about the pain you went through to get this data, nobody.” It would be like me saying, “Here’s my book. But I’m going to start with 40 pages on all the agony that I went through to show you how important [it is], and then you can read my book.” It would be dreadful.

How did you land on the 10 to 14 age group as the target audience for your storytelling?

This is when it’s still OK to be enthusiastic about something. And when you actually have the knowledge base to understand. It’s also the time that you begin to have those feelings of exclusion or loneliness, emotional things that [an author] can tap into. So you’ve got some enthusiasm, you’ve got some anxiety about the world. And you’ve got the mental apparatus.

It’s also the time when we start losing kids in science, right? We start losing girls at that age, we start losing kids of color, and we don’t want science to be run by a bunch of White guys. We want that diversity of thought. Even if you don’t become a scientist, if you start having an appreciation for science, that’s going to make you a better voter, it’s going to make you a better citizen. I’m not delusional—I’m not sitting here in central Pennsylvania thinking, Jay’s turning the ship with his books. I’m not. But [my wife] puts my books in her [seventh grade] class. Every year, there’s one or two that will read all of them voraciously. So there’s a couple kids there that may have been affected. And I think that’s the goal.

Vicky Smith is a young readers’ editor.